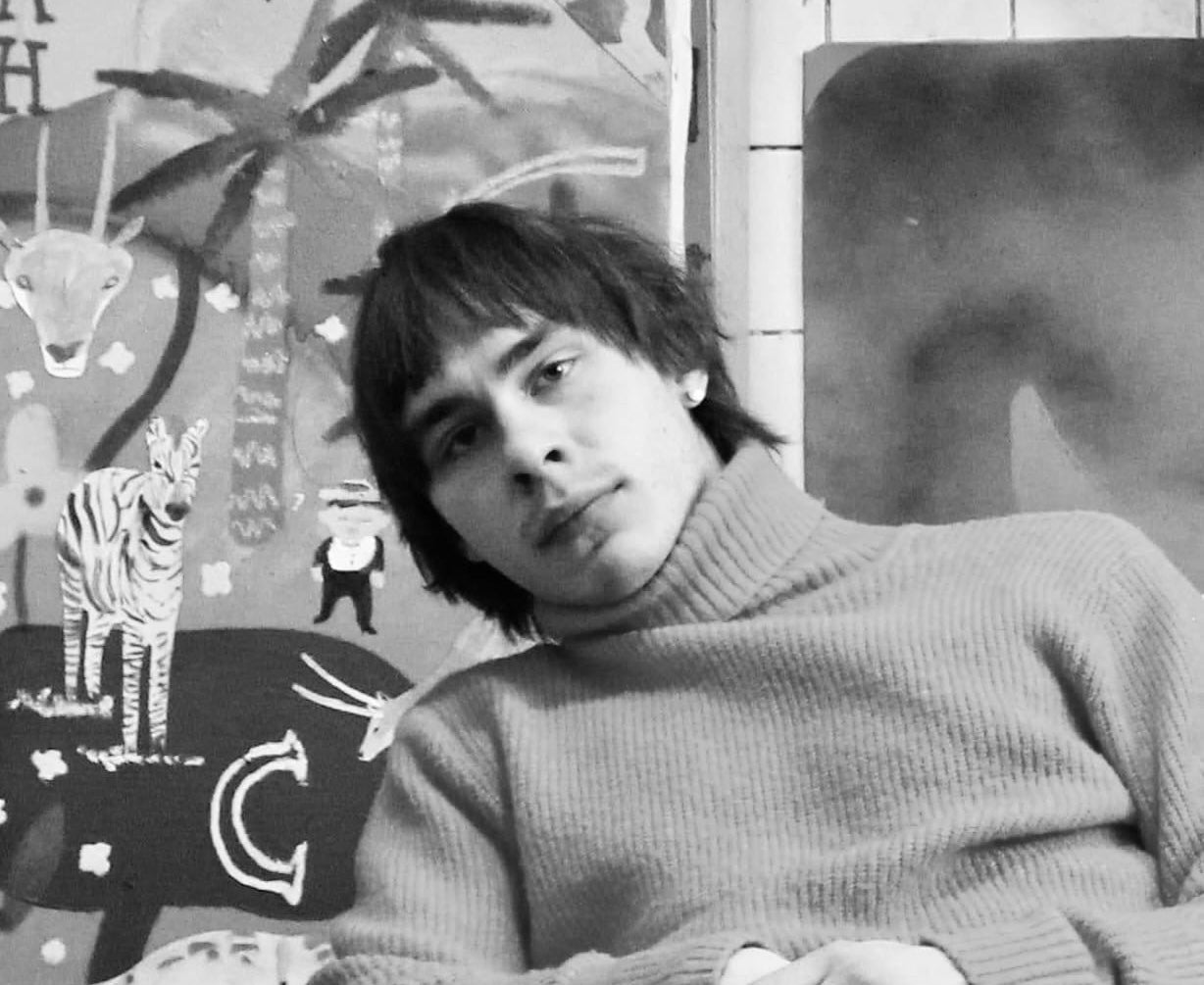

Yakov Khomich is an artist unafraid of experimentation. His creations — leopards riding elephants, plush bears, paintings sprinkled with meme phrases — have captured the attention of many collectors.

We visited his studio to talk about his path into art, his views on academic versus naïve portraiture, and what it’s like when your brother is also a well-known artist.

-

Where did it all start for you?

“I’ve been drawing since childhood. Both my elementary and secondary schools specialized in visual arts. Alongside Russian and Math, we had classes like painting, drawing, and decorative composition.

After ninth grade, I enrolled in a theatre college to study scenography, and later I studied at VGIK. So yes, I do have a solid academic foundation. Our teachers in college were mostly graduates of the Surikov Moscow State Academic Art Institute.At VGIK there was a bit more freedom in terms of how you learned — but you had to earn that freedom. Through bad grades, misunderstandings, and countless arguments, you had to fight for your right to self-expression.”

-

Does that academic background help you now?

“Yes, absolutely. I was lucky because working in theatre and cinema forces you to experiment with different textures and materials. That gave me a lot of knowledge and experience — how to use literally anything: glue, metal, wood, you name it — in my paintings and sculptures.

It gives you a certain freedom — you’re not tied to a single medium like oil or acrylic. You can work with anything, as long as you know how. The only challenge is to come up with an idea and find the right material to bring it to life. But that understanding comes only with time, experiments, and failures.”

-

Which is harder: an academic portrait or something in the style of your current work?

“I wouldn’t say it’s about difficulty — it’s about technique. Even in my spray-painted portraits, the principles are the same as in academic painting. My figures aren’t distorted; their proportions and colors are natural. I still work with light, shadow, volume, and form — the difference is, I’m doing it with spray cans instead of brushes and oils.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about returning to more complex, multi-layered compositions — painted realistically. I respect artists who work in the traditional manner. I think many of them could pick up spray cans and create something stunning.”

-

So, for you, academicism still holds value?

“Yes. Academic painting is like a unique language — it can show the viewer something no other style can. Abstraction is about pure feelings and emotions. Academicism is the opposite: it recreates something almost exactly as you see it before you.

Then there’s hyperrealism — I dream of trying it someday, though I know it would be incredibly challenging and time-consuming. Hyperrealists can paint a single dewdrop on a dragonfly’s wing. It’s insane. I have a lot of respect for that.”

-

Recently, you visited the Naïve Art Museum in Yekaterinburg?

“Yes, Gosha and I went there. There were works by many well-known naïve artists, even Leonov. You don’t often find yourself in such museums, but when you see those paintings up close, you realize how meticulous they are.

For example, there was an 80×80 cm landscape with a strip of sky, tiny people, little cars, and every single blade of grass carefully painted. You start thinking about the scale of time and detail — like how, for an ant, crossing a road is a life-long journey. That’s how I felt looking at that grass.

I’ve been craving that kind of precision lately — spending a month or two on a single canvas, not working in flat color blocks but focusing deeply on details.”

Le lac d'Annecy №1

Yakov Khomich

Yakov Khomich (b. 1997) is a contemporary artist based between France and...

-

You work with so many materials — ceramics, collage, acrylics. Do you have a favorite?

“It’s hard to pick one. Lately, I’ve been working more with spray cans — my series of blurred paintings with text was done entirely in that technique. I’ve also been experimenting with construction foam to create soft, plush, cloud-like animals.

But here’s the thing: you never really know how a material will behave over time. I test as much as I can — I stretch and treat my own canvases — but I can’t guarantee how a piece will look in ten years. I’m upfront with collectors about that. Experimentation sometimes comes with risks, but I’m not the first — Impressionists repainted the same canvases dozens of times. You can even find portraits painted on the backs of landscapes!”

-

And how do collectors react to these experiments — like your foam pieces?

“It varies. My work comes in series. For instance, when I was in France, I created lots of small graphic works using pastel, pencil, and watercolor — light, bright, almost like stained glass. I painted them outdoors, not locked up in a studio, so they carry that airiness.

Then you have my foam animal paintings. Some collectors buy several of those. Others prefer my tropical series — leopards, jaguars, and riders. And then there’s the spray-can series, which is more contemplative, almost meditative.

Sometimes the same collector buys from multiple series. I don’t try to be “versatile” deliberately — it just happens. I like exploring different visual languages for different themes.”

-

Your paintings often feature short phrases or captions. How do you choose them?

“At first, memes inspired me. A year ago, I found old, blurry photos on my phone — failed shots, really — and realized I could use that aesthetic to reflect our current state of mind. Richter blurred his canvases, too — like watching the world from a moving car.

Sometimes I start with an image, sometimes with a phrase. I get them from everywhere — memes, books, films, random quotes. I even tried eavesdropping on conversations, but didn’t hear anything useful.

The important thing is contrast: the text shouldn’t literally describe the image. It should create tension or a new layer of meaning. For example, there’s a painting of a swan with the caption “See you tomorrow?” — “No.” The swan has nothing to do with the dialogue, but it feels like a fragment of subtitles from some unseen film. That’s what I’m after.”

-

-

"Much of what I do is rooted in observing human behavior, childhood narratives, and fragments of cultural memory. "

-

Le lac d'Annecy №1

Regular price $900.00Regular priceUnit price per -

Le lac d'Annecy №3

Regular price $900.00Regular priceUnit price per -

Le lac d'Annecy №2

Regular price $900.00Regular priceUnit price per -

Le lac d'Annecy №4

Regular price $800.00Regular priceUnit price per